In The Myth of the A Player I poked at the conventional wisdom of what makes an “A player.” Most early stage VC filters are tuned to be consensus-right not contrarian-right. That can generate good returns but not necessarily great ones. Contrarian bets are what drive big fund returns, as Ed Suh explains:

Of course, the contrarian companies are the ones that end up producing the *best* returns (through a combination of lower entry prices, less dilution from greater capital efficiency, & TAM expansion as they tend to create net new markets). We all know that, in theory. But it's a long and windy road to get there, and everyone else is rolling their eyes along the way.

Ed Suh, Alpine VC

VCs should be mavericks chasing mavericks. But there’s also an inescapable need for proof, to LPs, other VCs and themselves.

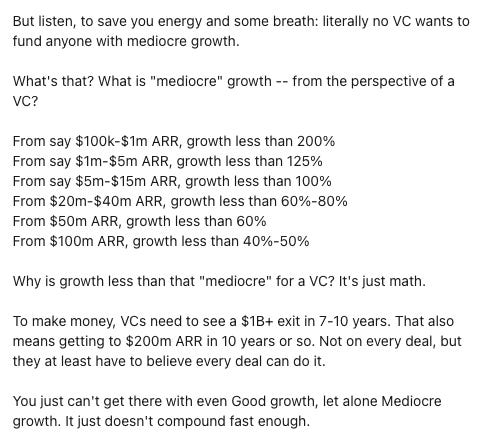

This post from Jason M. Lemkin from SaaStr is a great example of consensus thinking about what constitutes proof in 2024:

You won’t catch me arguing that mediocre growth is better than fast growth!

But even it it’s true that “literally no VC wants to fund anyone with mediocre growth,” should it be? I bet those growth metrics are true for SaaS investors but what about everyone else?

Even with predictable B2B SaaS companies we know through experience that 200% growth early on does not mean long-term sustainable growth. It might not even mean product-market fit.

So why the focus and certainty that these are the right early predictors of success? Can we really identify true outliers by filtering for who has 200% growth at the early stage?

That doesn’t sound contrarian.

VC incentives make it harder to be contrarian

Being a truly contrarian investor is hard.

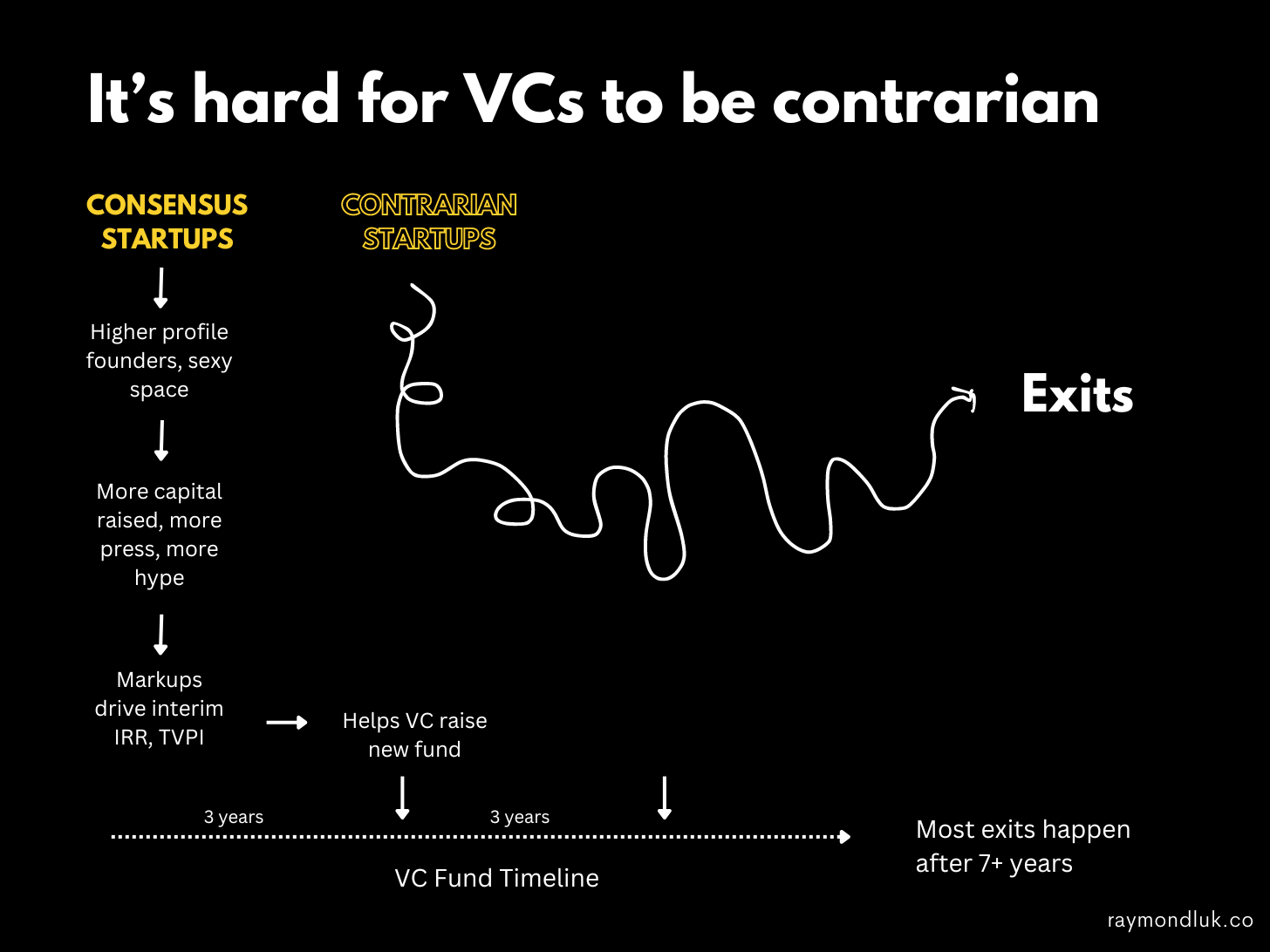

I already mentioned Ed Suh and you should read his excellent X post pointing out the structural reasons why it’s difficult to make contrarian bets.

Career wise, VCs need to show progress, usually in 2-3 year increments. Junior associates want to get a promotion and senior VCs want to move up to a bigger/better firm or start their own.

VCs start raising their next fund within 3 years1. In the absence of exits, which won’t happen for awhile, it’s natural to gravitate to startups that look like winners (even though you can’t know yet).

Aside from exits, which are virtually impossible to come by that early, markups are the interim markers that supposedly demonstrate positive progress. A company that is re-valued at a higher mark from a new investor can carry a VC's portfolio, driving interim IRR and TVPI. What kinds of companies tend to get higher markups faster? The ones that are perceived to be the "hottest": high profile founders with pedigreed backgrounds, sexy spaces that are in favor.

Ed Suh

If that doesn’t sound contrarian it’s because it’s not. But perception is important in the venture game:

VC is very much an image game before it is a cash distribution game. If you're in high profile companies alongside well known investors, you're perceived to be a good investor yourself (regardless of the entry price/stage or actual returns from those investments).

Here’s my visual summary:

There are very strong structural reasons why it’s easier to choose deals that appear consensus right. Those deals generate early signals that feel good and fuel career growth (and help raise the next fund).

Those other deals? The outliers? Not so much.

Psychosocial barriers

It’s easy to challenge VCs to be non-confirmists but there are psychological and sociological reasons why it’s difficult to stand out.

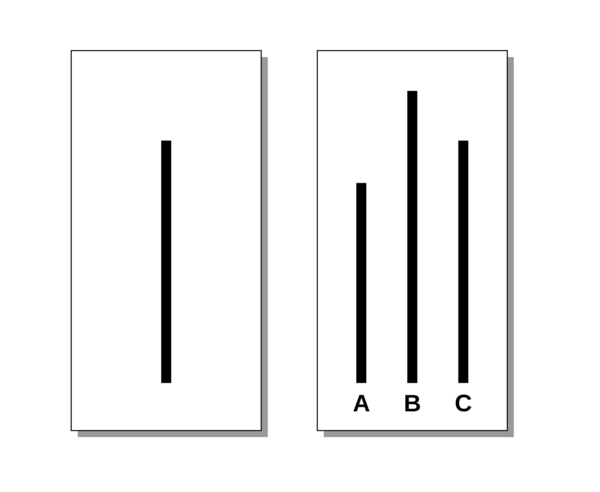

In Breaking Conformity: The Power of One Lone Voice, Brett Beasley describes the following experiment. A person is given the card on the left and asked which line is matched on the right. It’s C. Easy right?

But in the experiment 75% answered incorrectly. Why? Because there were actors in the room who had been trained to vote for the wrong answer. When the group voted for the wrong answer most people went along with it.

This type of groupthink happens in many areas of business and in life. It happens in VC where there is pressure to show quick progress through signals like early growth and being part of a hot deal.

Left vs Right Brain Investing

All VCs should have a background in philosophy, not finance.

I think Scott Hartley would agree. He’s a VC at Everywhere Ventures and the author of one of my favorite books, The Fuzzy and the Techie.

He does a great job challenging the idea that some startups are obviously awesome (to steal a phrase from April Dunford). That sentiment is driven by left brain logic and an over reliance on early, logical signals:

…Left brain investing by logic often falls into the trap of Zeno’s Paradox. The thing you think should happen just never quite seems perfect. The team isn’t quite strong enough. The traction isn’t quite there. The valuation is just a bit too high to support the easy decision. If only things were a little different you could see it working. If only you were a little earlier you could rationalize the valuation. If you hold onto control too tightly, you will logic your way out of doing the deal. Left brain investing is great for growth-stage investor mindset. One looks at every angle and forecasts every downside explaining why it doesn’t make sense to invest. You're combating price, rather than purely systemic or survivability risk, so there's not just a binary of ways to lose, but a whole quantum of ways to lose, so it takes a lot of care. But if you hold the steering wheel so tightly as a pre-seed investor, if you fail to suspend logic to believe that the crazy can in fact happen, you might end up with a portfolio of safe doubles, but you’re never going to find true outliers. If the world is logical and calculating, you need to be skeptical and open to be different.

Scott Hartley, Everywhere Ventures

Read about Zeno’s Paradox here (it could kick start your VC career)

I think VCs instinctively know how to suspend logic when they meet a great entrepreneur. But just like it’s easier to say you’re contrarian than to be one, few investors openly talk about the importance of non-standard or unusual signals.

The best companies are contrarian and right, and logic alone would never get you there. Founders move fast, and have a resolution about them that sees past logic, past the need to control outcomes with reason. Similarly the believers in these companies also had the humility and childlike wonder to believe that the logical impossibility was in fact the only way the world was going to go. To them it was as obvious as Achilles beating the tortoise in a race. We all need to observe our own limitations and biases in how we approach problems. We need to ask ourselves, “how do I see the other side of the coin, how do I question my own logical impediments to get to the obvious answer?” Outliers hide in plain sight.

That beautifully sums up how VCs can benefit from a dose of philosophy with their finance.

Confessing to your LPs

It’s one thing for GPs to embrace the discomfort of backing outliers. It’s another to convince LPs. Imagine a VC fundraising desk that crossed out all the spreadsheets and market research and replaced with: Trust Us.

Hummingbird Ventures, who I wrote about in my last post, is the source of another fascinating real-life story about a GP having “the talk” with their investors.

At some point, early in their fund, founder/partner Barend Van Den Brande decided he needed to make a confession to his LPs:

“I said to my own LPs, ‘Listen guys, we’ve got to do a confession’…He proceeded to run through a hypothetical with the collected LPs. Imagine if Hummingbird had invested in all of the good companies it had seen and none of the bad ones, that it had, in effect, a 100% hit rate. How would such a record have been possible? What rationale could have led to that outcome, with the benefit of hindsight? “I told them, ‘Listen, I know this sounds like a bit like of an iffy or a shaky type of exercise. But the only way to do that is to put 80% on the founder. And you know what? I’m taking all of your money here, and for the last two years, we’ve been leaning in a direction which is super uncomfortable.’” Hummingbird could say what the assembled LPs might have wanted it to say, to spout acronyms and facile frameworks (“we are really good at acronyms in the tech industry,” Van den Brande remarked), but that wasn’t the reality of their approach. Hummingbird believed that founders were four-fifths of the equation – that was its confession. “‘We do this with your money, you need to know.’”

Mario Gabriele (The Generalist) in The Best Venture Firm You’ve Never Heard Of

Almost all early stage investors say they invest primarily in founders. But if you take the time to read about Hummingbird you’ll realize that this is not idle talk or platitudes. This was a doubling down on some truly unusual criteria for identifying outlier founders: trauma in their history, neurodiversity and not turning away from founders that looked like automatic passes for other VCs.

This worked out great for Hummingbird’s LPs but would be challenge for most.

The Power Law Challenge

Everyone knows about the power law in venture capital: 80% of the returns come from 20% of the deals. That obviously does not mean that 20% of all investments will be huge winners.

It does mean that being contrarian is essential, not optional. Otherwise even with reasonably good bets you end up with 20% of the return potential, leaving 80% to the contrarians.

I’ve mentioned only three obstacles to being contrarian, but they are important ones:

- The venture model has built-in incentives that make it harder to make outlier bets

- Most people are influenced by groupthink and their own biases

- It’s more difficult to convince LPs to back a contrarian strategy

Funds can generate better returns, and more outliers will get funded, if VCs are more aware of how these obstacles subtly discourage them from being truly contrarian.

https://differentfunds.com/research/vc-fundraising-cycles/ ↩