This is part four of a series on ownership for founders. This isn’t a series on how to raise, but how to understand different owner perspectives, including your own.

I hate using spreadsheets to teach cap tables

Most people just tune out. Excel templates are good for learning low-level details but not good for helping founders understand the overall mechanics.

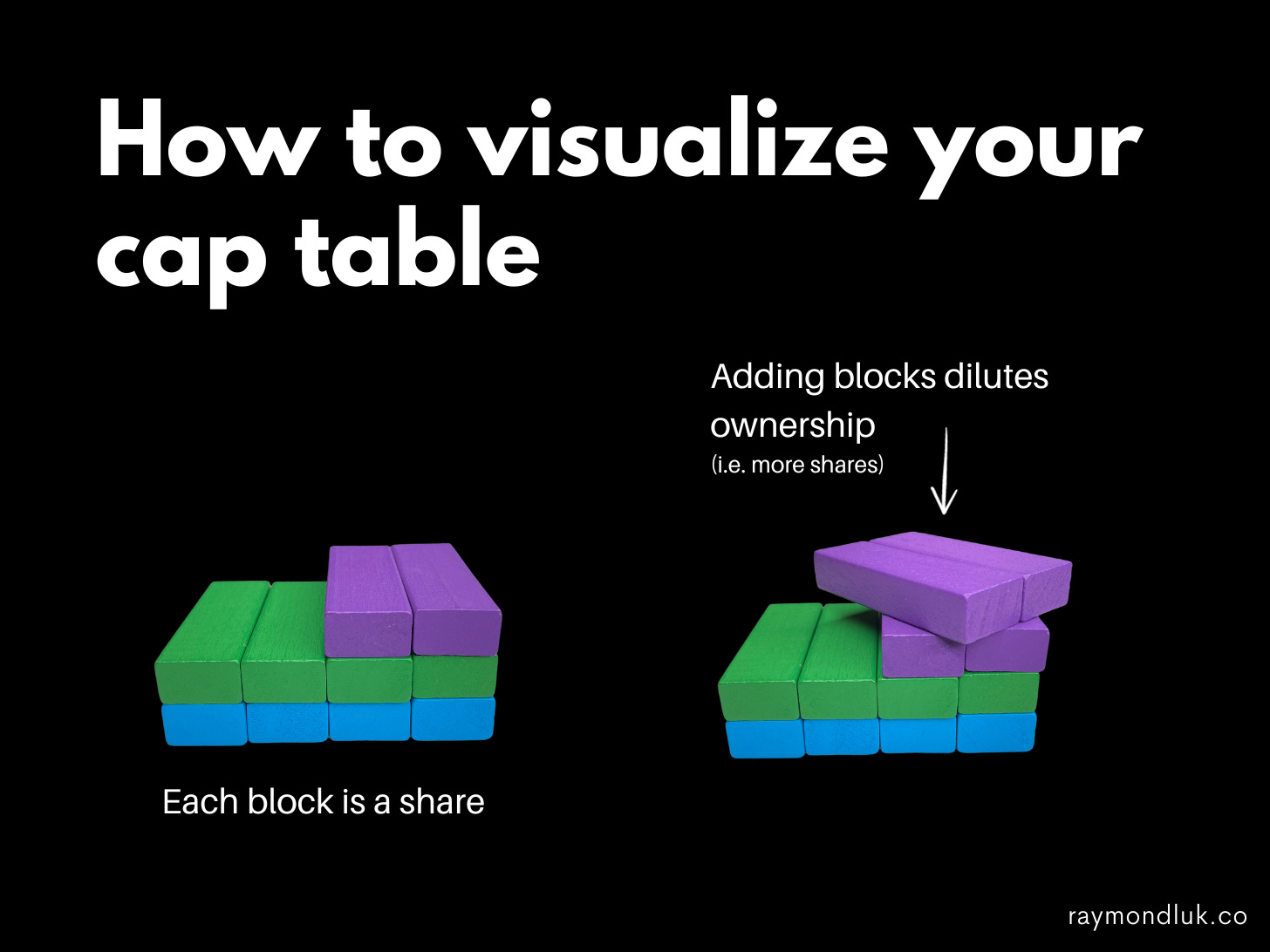

So I created a new way to explain all the elements of a cap table using Jenga blocks.

Thanks for reading A Leap of Faith! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Instead of thinking of % ownership, you should think about the number of shares you own. When you sell the company each ‘block’ gets a share of the assets. So every block added means everyone owns a little less, i.e. you dilute.

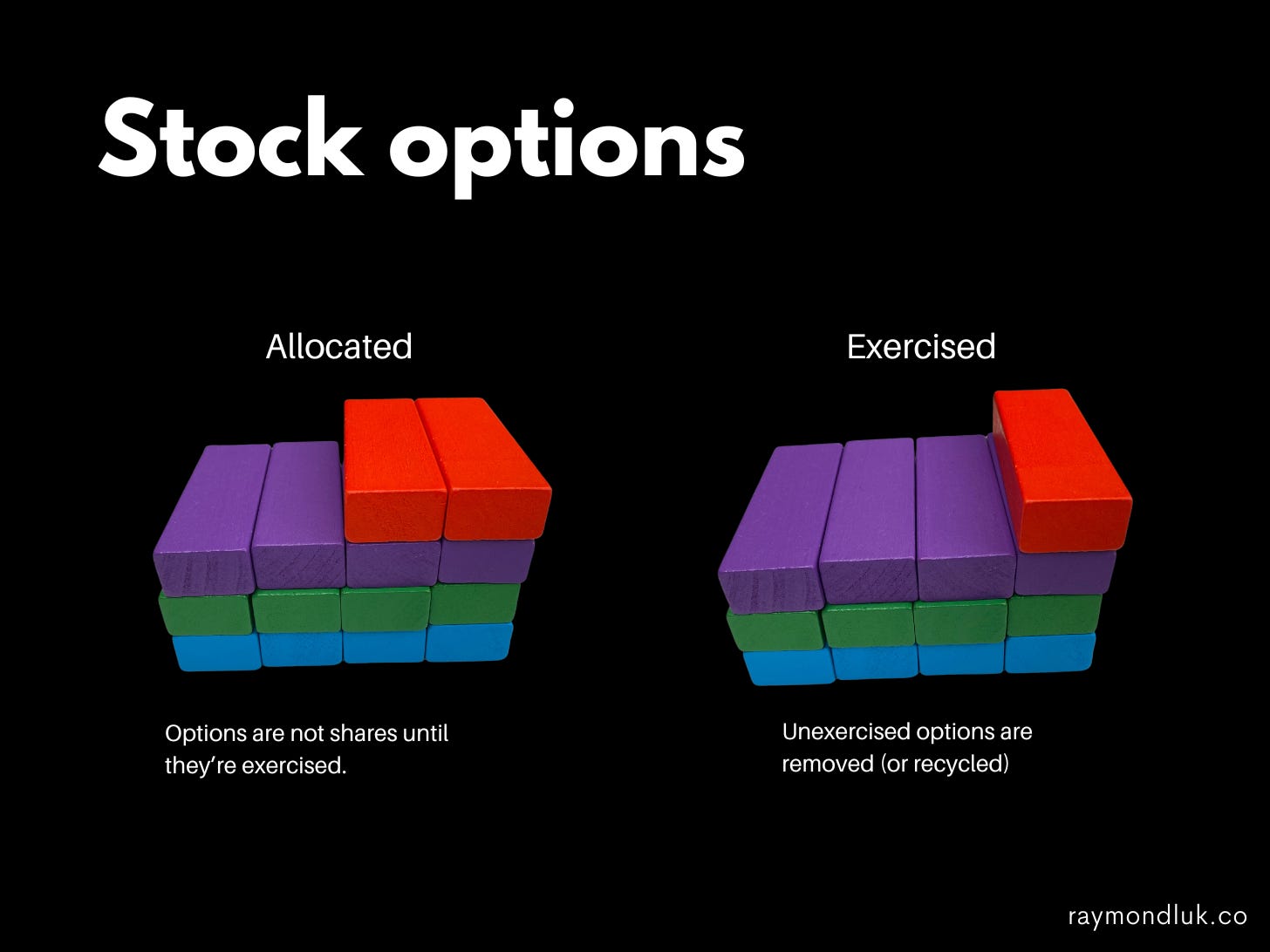

Options convert to shares later. You can reserve space on your cap table (fully diluted) or remove options not yet exercised.

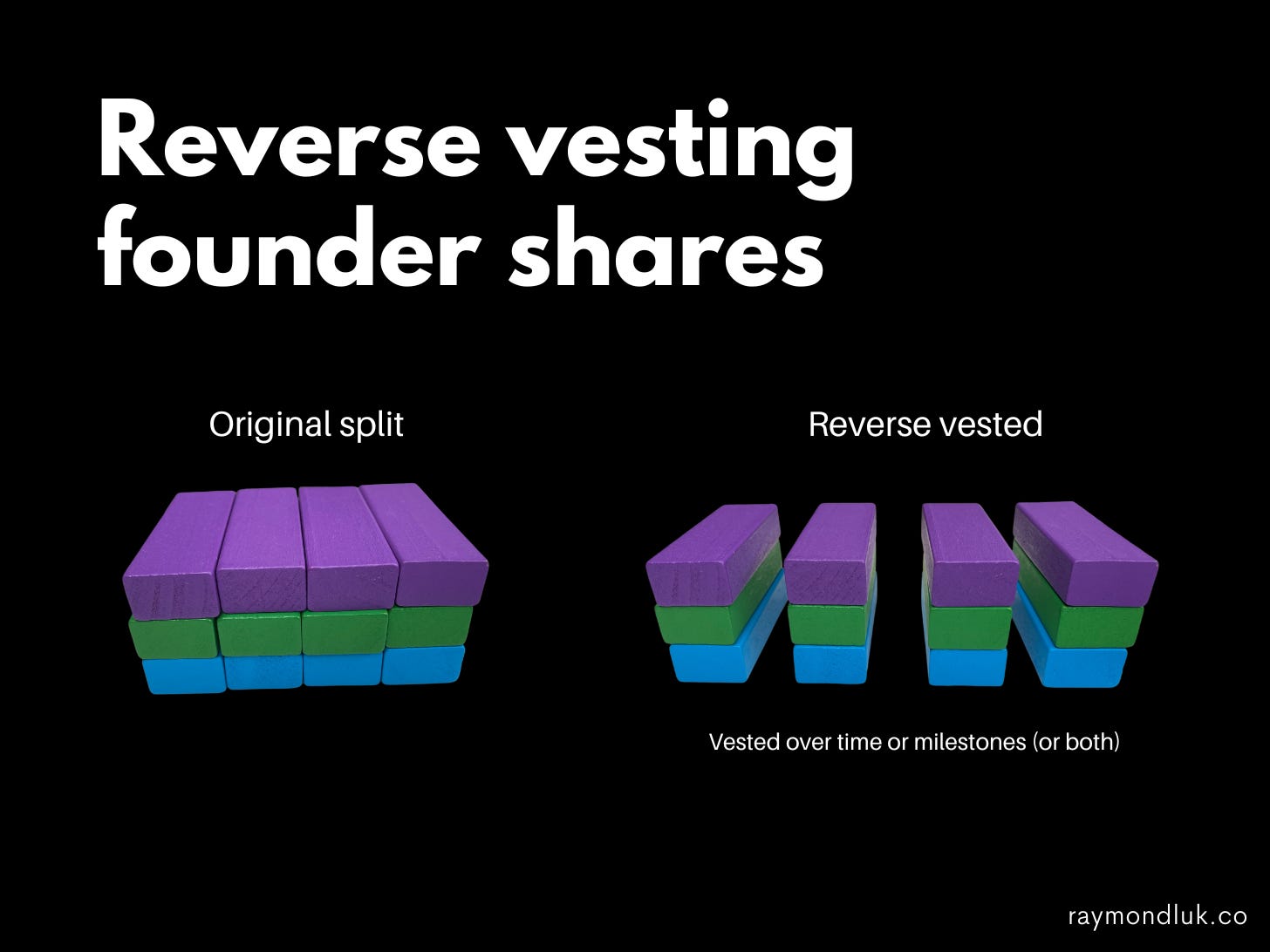

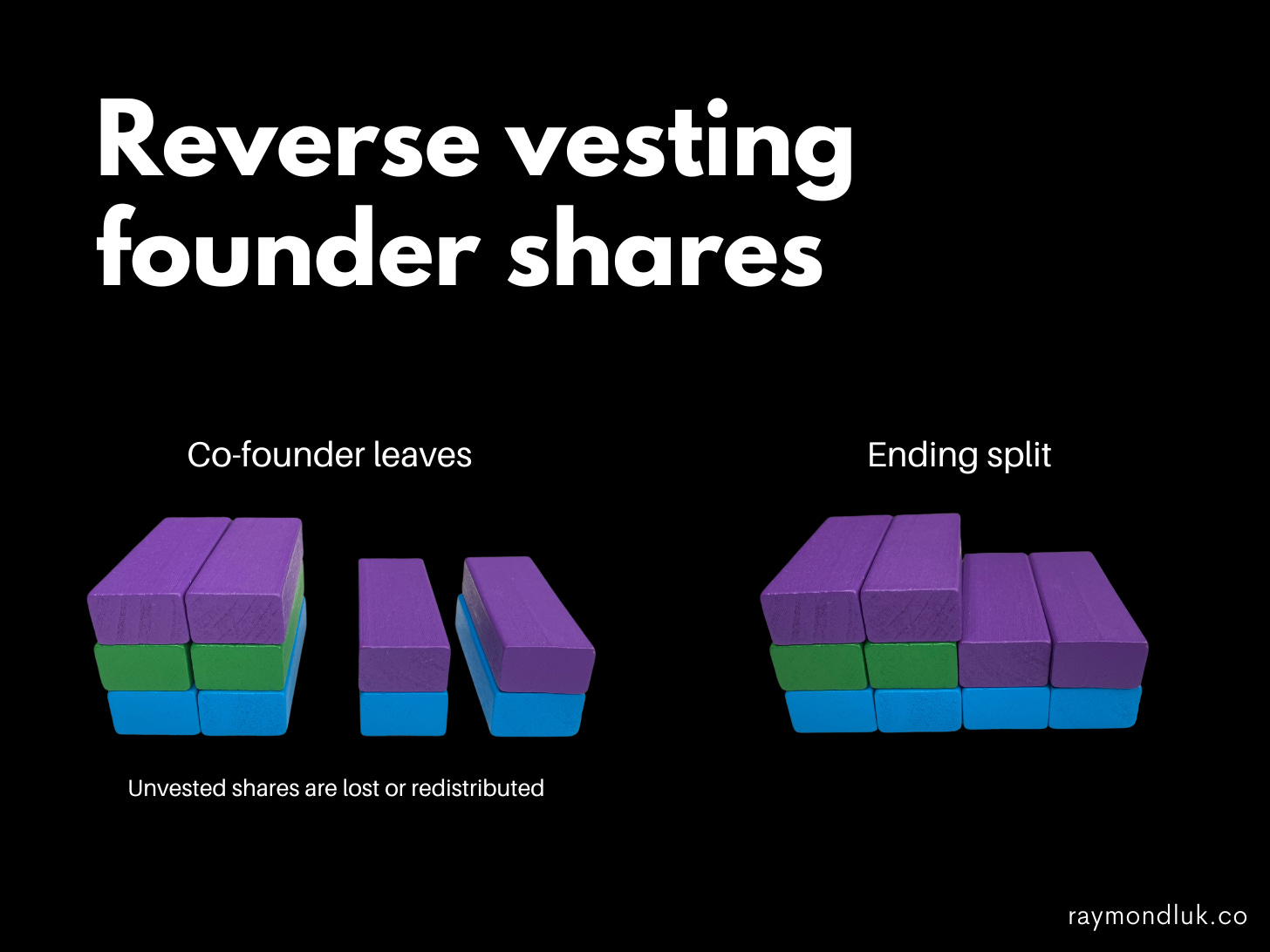

Most cap tables have a base of founder (common) shares. But those could be reverse vested, i.e. they are released over time or based on milestones.

This is more fair if a co-founder leaves or can’t contribute what you agreed to. They don’t lose shares they earned.

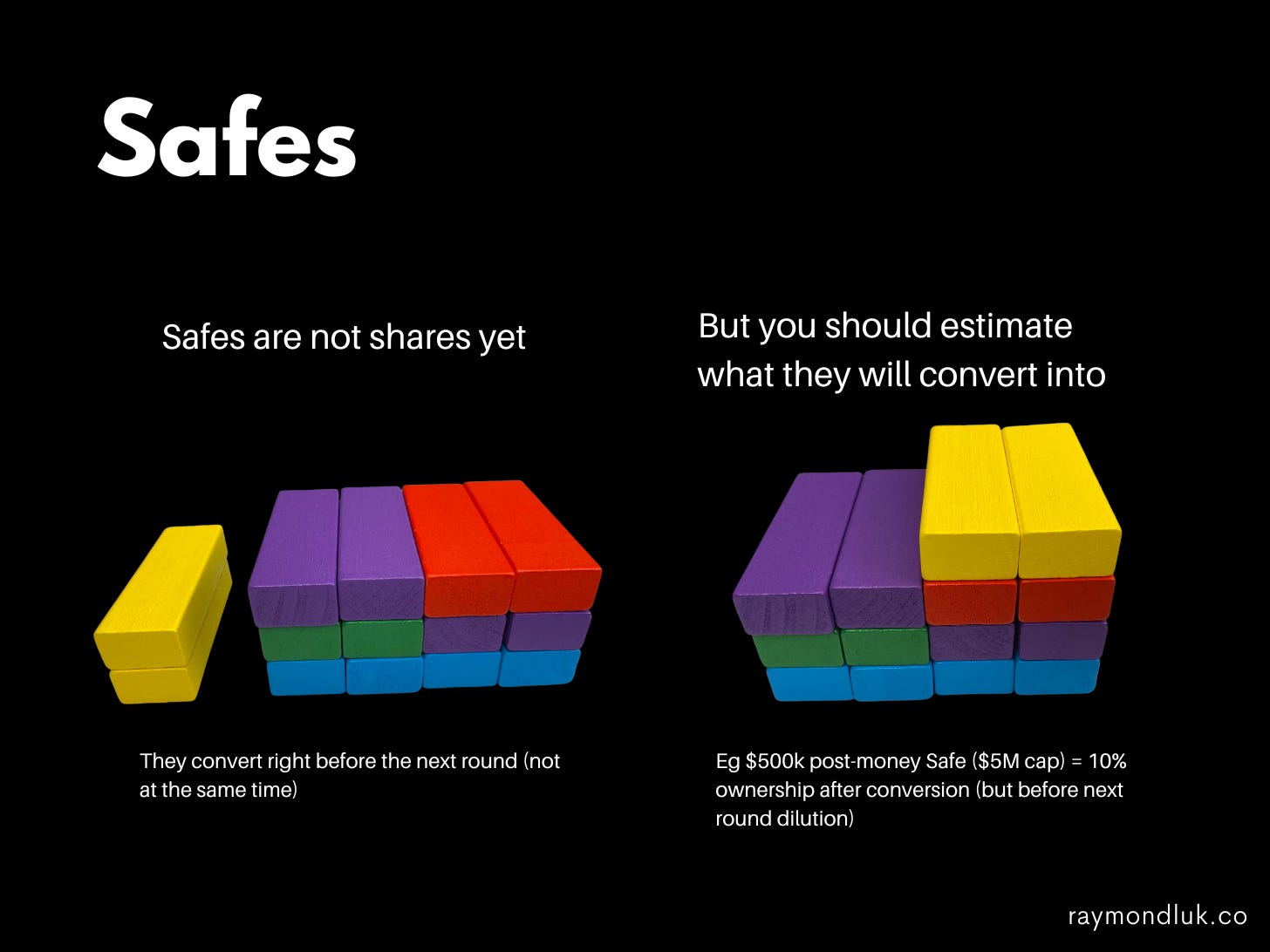

Safes, and convertible notes, are like options: they’re not shares yet. But be careful about thinking “you’ll deal with them later”.

Especially with post-money Safes (the most popular), it’s easy to estimate what they convert into, and easy to underestimate how much you’re giving up.

This is especially important if you find yourself adding more and more Safes (stacking). One thing people do not realize is that post-money Safes have built-in anti-dilution. Even if you raise multiple rounds of Safes, everyone’s % is locked in. has a good explanation here.

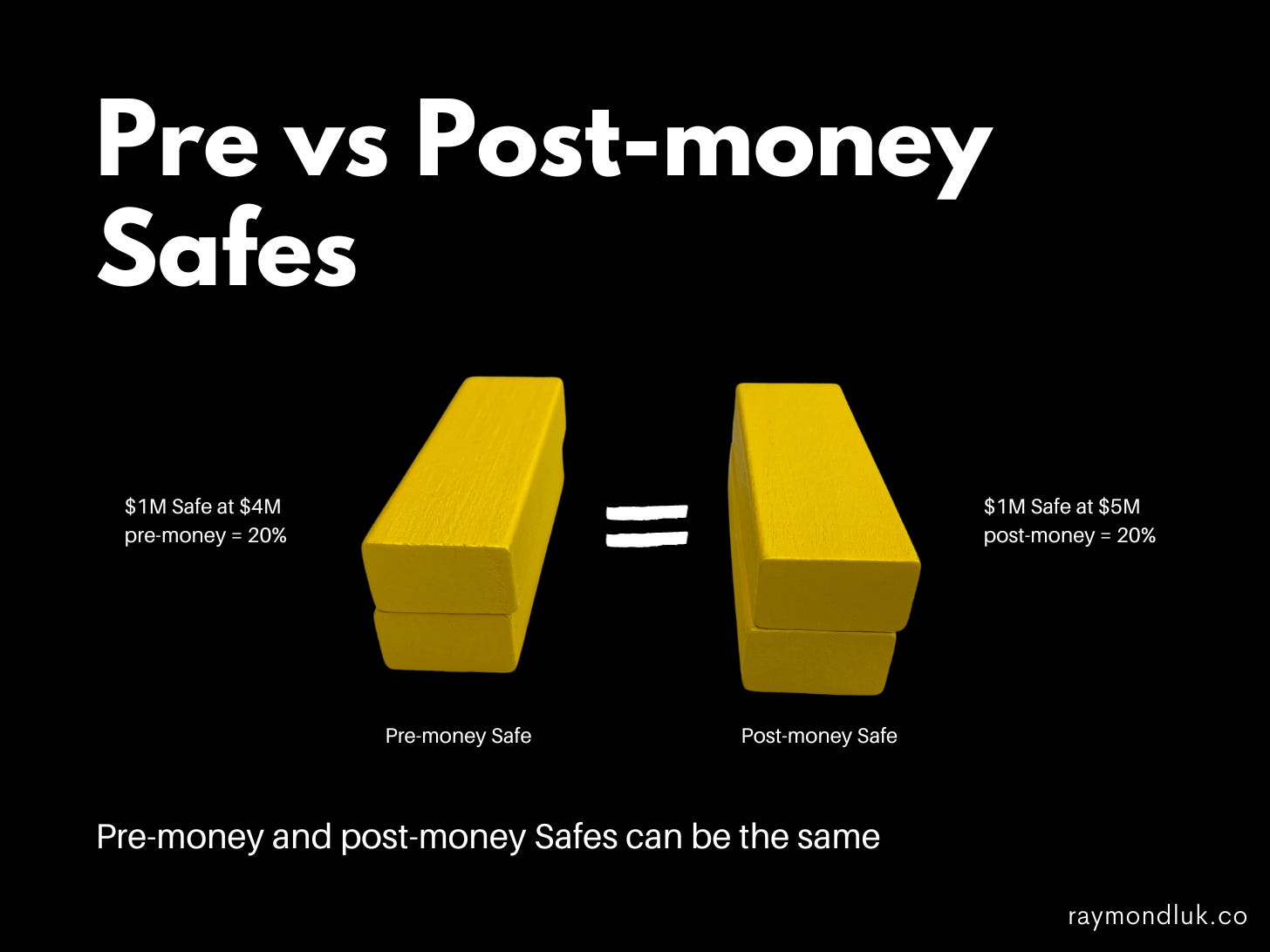

There are pros/cons of using pre- or post-money Safes. But in some instances they can work out to exactly the same ownership.

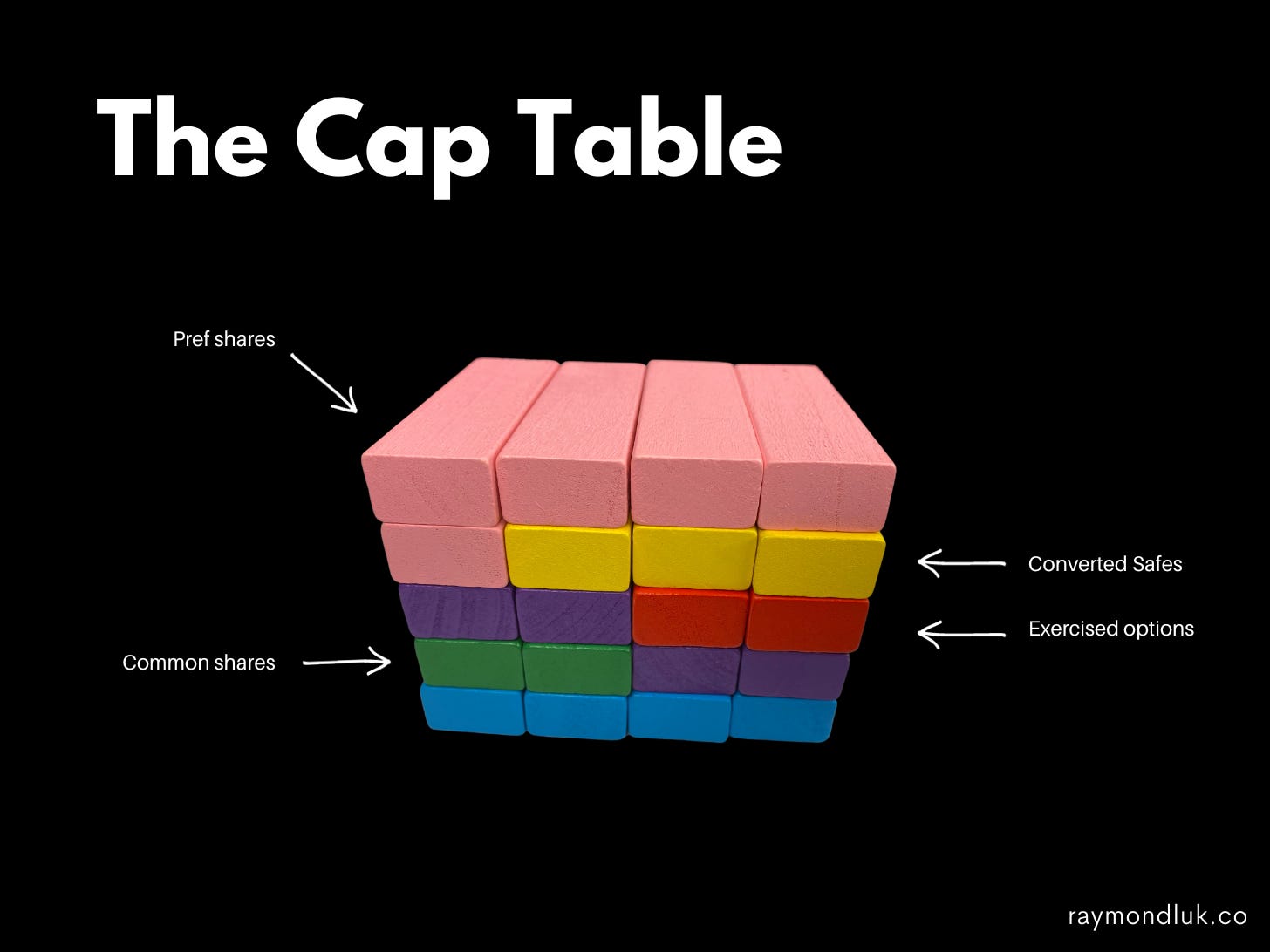

Finally, this is what a seed-stage cap table could look like.

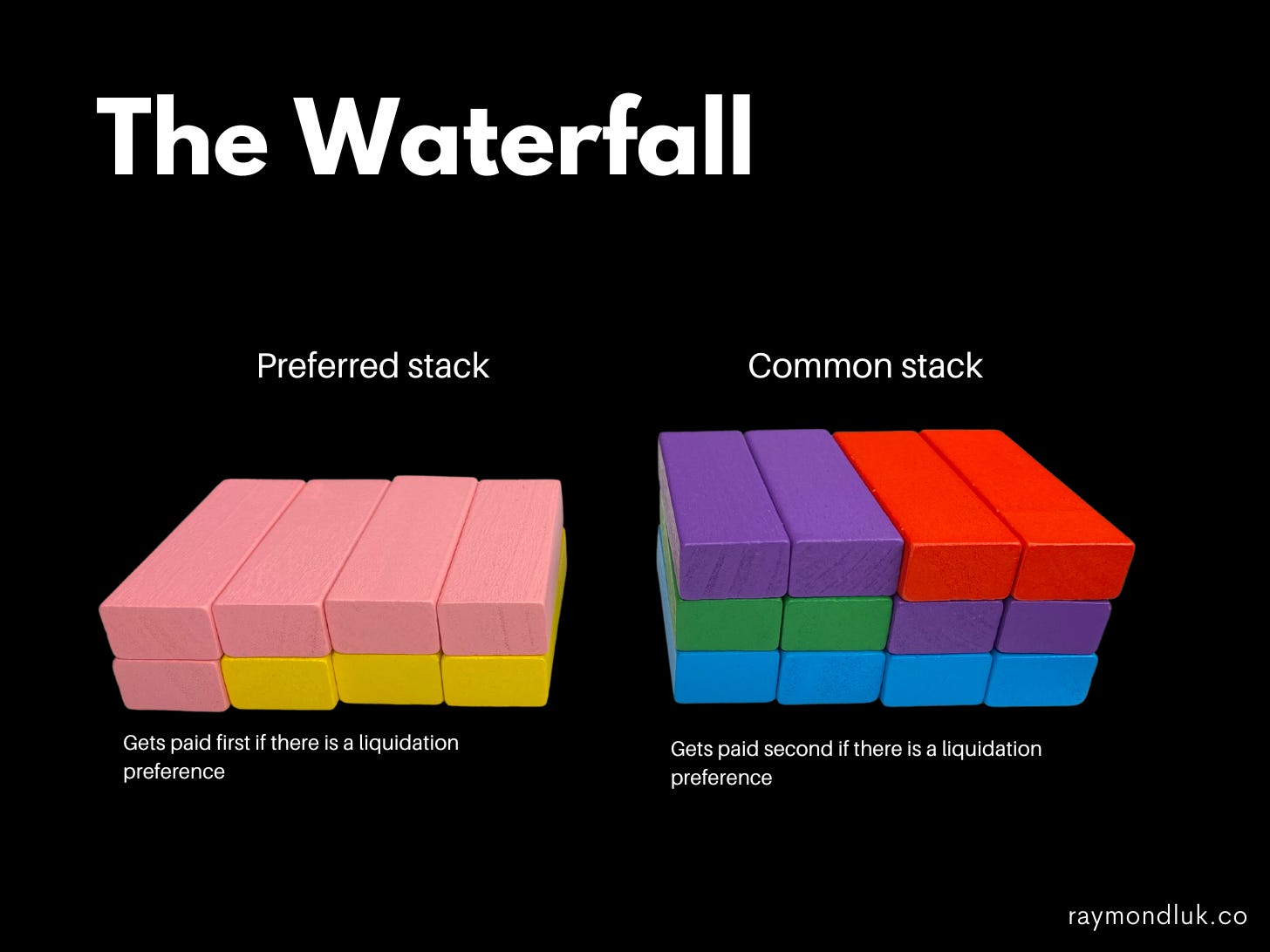

On an (early) exit, the preferred stack (including Safes that converted into pref shares) would get paid first.

That’s assuming there was a liquidation preference and the sale price was low enough that not everyone could get paid their share.

There is more that could be done with this analog approach: multiple classes of shares with different terms, secondaries, downrounds and exit modelling. Lots of wooden blocks.

But this covers the most common types of shares on the cap table and the core mechanics. No math!

If you like cap tables and hate math, share this post! Or maybe you love math, share anyways.

Further reading:

Previous posts in the series:

What does it mean to be a shareholder?

Raymond Luk • Aug 15, 2023

Ask any entrepreneur and they’ll tell you they feel immense pride in owning something. It’s a prime motivator. What does it actually mean to be a shareholder? It’s an innocent question that I doubt founders spend time contemplating. Maybe they should. Because in my workshops I’m constantly asked about technicalities of stacked SAFEs, multiple liquidation…

Read full story →

Understanding Angel Investors

Raymond Luk • Aug 22, 2023

This is part two of a series on ownership for founders. This isn’t a series on how to raise, but how to understand different owner perspectives, including your own.

Read full story →

Safes and Convertible Notes

Raymond Luk • Sep 12, 2023

This is part three of a series on ownership for founders. This isn’t a series on how to raise, but how to understand different owner perspectives, including your own.

Read full story →