Here’s to the crazy ones.

Be contrarian and be right.

Visionary. Outliers. Mavericks.

If you’re a founder or a VC you identify with those statements, or aspire to them. The startup gene pool is built on this notion of non-conformity. We don’t have jobs, we have missions.

Let’s question those founding myths. Not that I don’t believe in mavericks, by the way. Founders must be outliers to succeed and VC math requires a contrarian view.

But something has always seemed off when I see how early stage startups interact with early stage VCs. There’s so much focus on traction, market size, CAC:LTV and the pedigree of the team. Founders have no choice but to adapt their pitch to suit these questions.

But it all seems more focused on finding consensus, not being contrarian.

In this post I’m going to explore the myth of the “A player”.

Thanks for reading my newsletter. Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.

Pre-Idea Stage Fund

In 2009, I co-founded (with Ben Yoskovitz, Ian Rae and Alistair Croll) an early stage fund called Year One Labs.

Many VCs say they invest in founders but we doubled down by making a rule: we would invest in founders who didn’t even have an idea for a company yet. No pitch decks, no competition slides. We were pre-idea.

What we did care about was finding ways to get to know the founders at a deep level: their creativity, work ethic, technical and interpersonal skills and their entrepreneurial DNA (no, we did not swab anyone). We found hackathons were the best way to test that and we ran hackathons with Google and others.

Most of our founders were first timers and some of the team members only met through our hackathons.

This thesis worked well enough for that cohort to have generated a 7.5x cash-on-cash return for the fund.

I’m not suggesting our model was the best but it was consistent: when you say you only care about people then logically you shouldn’t screen for idea or pedigree.

I think too many early stage investors have incorrectly tuned filters. They’re looking for signals of excellence but not signals of being contrarian.

The A player trap

Everyone agrees that to build a successful startup you need “A players.” Every VC is looking for them in the pitch deck. Founders feel they need to raise enough money to attract them.

But is this crucial to building a successful startup, or even desirable?

First, how do you recognize an A player? Assume that when you ask who is an A player everybody raises their hand.

What signals do you look for?

- Repeat founders or prior startup experience

- Relevant industry experience

- Work experience at large, successful firms like Google, Microsoft

- Impressive academic credentials, especially for engineers

- Social signals like who you know (your network), how we got introduced

What if those were not reliable signals?

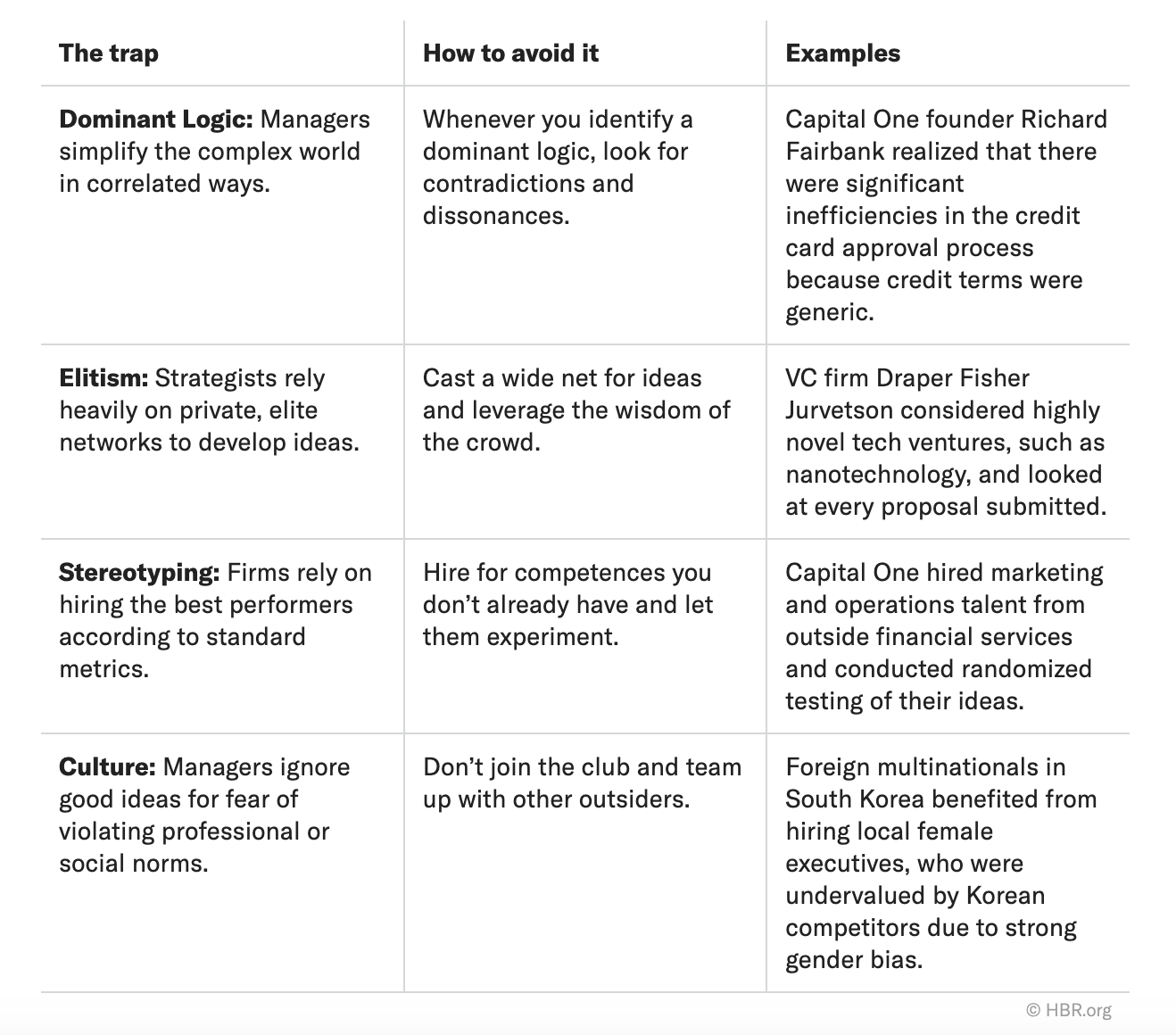

In How to be a smart contrarian (Harvard Business Review, 2021), Chengwei Liu points out that outliers are seldom found in traditional ways. In fact, you have to fight against norms that drive you, and everyone else, to keep coming up with the same answers.

He lists four ‘traps’:

Dominant logic

People tend to solve complex problems, like picking which startup to invest in, in correlated ways. Ever read advice on “how to attract VCs”? That represents a consensus view on being investor-friendly. It can be good advice but if you’re a VC and you find a startup that checks all the boxes, you will likely have found a consensus opinion, not a contrarian one.

Elitism

Venture capital is highly elitist. Founders are insecure about lacking some aspect of pedigree, whether that means living outside the Bay Area, not having graduated from MIT or YC, or not having a successful VC-backed startup on their LinkedIn profile. Are those advantages self-evident or should we question them?

Stereotyping

What are objective measures of being an A player? One of the world’s most successful VCs, Hummingbird Ventures (more about them later), defines an A player as someone who has trauma in their past. That is not on your typical VC list of positive signals.

Culture

VC still relies on elite networks to filter dealflow. That’s the “how you’re introduced to me is important” rule. It works to ensure only quality founders get through. But what if you’re looking for outsiders, crazy ones? That system filters them out.

Liu is talking about management in a broader sense, but I think it’s a great cheat sheet for checking your filters and assumptions. Founders should ask themselves why it’s important that co-founders have scaled a company at a well-known tech firm. That doesn’t guarantee they can help you find product-market fit.

VCs should question if being a hot founder, or a hot deal in a hot space is consensus or contrarian. There are definitely top funds that by virtue of their size and reputation can consistently grab all three. But for everyone else it’s not a good strategy.

Here’s a fascinating example.

Hummingbird Ventures

I learned about Hummingbird Ventures in a post on . I wouldn’t be disappointed if you stopped reading this post right now and just read The Best Venture Firm You’ve Never Heard Of. It’s that good.

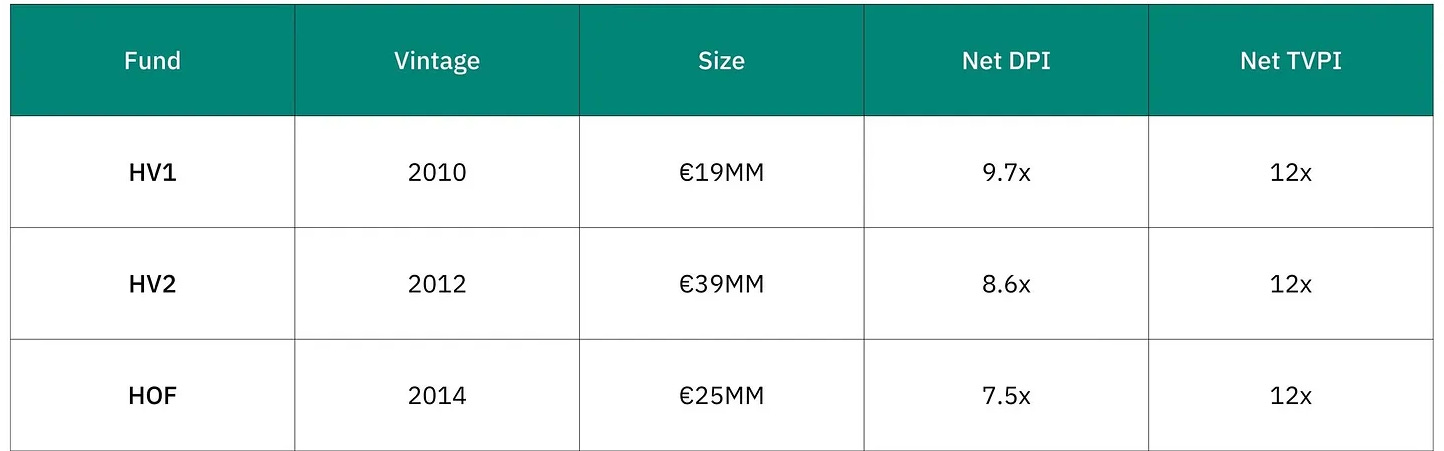

Hummingbird is based in Belgium, is not a marquee brand, and has focused on overlooked geographies like Turkey, to great success. But don’t believe me. Look at the returns of their first three funds:

That’s a stunningly strong track record if you’re skeptical of a truly contrarian VC fund thesis.

Here’s the thing. They’ve found success by redefining who they consider “A players.”

“Van den Brande and his team have driven such returns by ignoring much of the asset class’s conventional wisdom – and forging an extremely opinionated investing framework. Many venture capitalists emphasize the importance of the entrepreneur to their underwriting; none mean it quite as much as Hummingbird. For Van den Brande’s firm, the founder is not merely important; they are the only thing that matters. Forget about flocking to a hot new market or playing nice with Sequoia or Benchmark. If you want to deliver consistently superior returns, Hummingbird believes you need to find the most exceptional entrepreneurs on earth – not merely the top 1%, but the top 0.1%.”

Mario Gabriele

That’s an example of what being contrarian and right looks like as a VC. Here are two unconventional ‘signals’ they look for.

Trauma

Imagine meeting a VC for the first time where all the discussion is about your childhood trauma.

“Hummingbird believes that an experience with trauma is predictive. “All of the best people, in our opinion, have gone through a level of trauma. Where at some point life shows up and it’s not just all Tom and Jerry and cartoons. And it shows its teeth,” Van den Brande said.

Van den Brande recognizes that this is an uncomfortable position to hold. But it seems quite clearly to be an opinion with considerable merit. For some time, research has suggested a connection between childhood adversity and entrepreneurship.”

Neurodiversity

If you follow the logic of investing in founders, you wouldn’t stop your psychological investigation there.

“The second trait Hummingbird finds predictive is neurodiversity. The fund means that in a clinical sense. In particular, it has observed a connection between exceptional entrepreneurs and some degree of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). That may come with associated traits like bipolar disorder and dyslexia. “Just in the Hummingbird team, we have three people with dyslexia out of ten,” Van den Brande said. He hadn’t known that during the hiring process, only discovering as much after the fact. To the Hummingbird GP, it feels potentially indicative of a certain type of thinking or cognitive orientation.

Again, there is compelling evidence for Hummingbird’s observation. Research studies have demonstrated a connection between mental health issues and starting a business, another topic explored in The Generalist’s piece on entrepreneurship. The study we discussed found links with bipolar disorder, ADHD, and OCD.”

The more I read about Hummingbird’s story the more I questioned why their approach seemed so strange. Shouldn’t their abnormal be more normal?

Bad Pedigree

All of Hummingbird’s successful bets were on founders from non-traditional backgrounds, i.e. their pedigree sucked.

Take, Sidar Sahin, founder of Peak Games. This is what a first impression of him would have been:

“Before continuing, pretend for a moment that you are in the Hummingbird investor’s shoes. You meet an entrepreneur who has had both successes and failures. He is now building a new company, Peak Games, that seeks to capitalize on the “social gaming” market, a category that piggybacks off social media platforms like Facebook. It is competitive, with Zynga already three years old. He has a big, lofty vision. You find him slightly awkward.

You ask some questions. You learn about his past. About his wins and losses. You talk to references – they are unspectacular. You learn he has raised no money, and knowing the immaturity of the Turkish venture market, you can be confident that no capital will rush in.”

If you’re an early stage VC this is an automatic pass, not a $500k check that Hummingbird wrote in 2010, which (plus a bridge round) turned into a $276 million (54.4x) return.

Lean in to the outsiders

Not all outliers are good founders. Not all contrarian views are good investments. You still have to be right.

But purely from a returns perspective I don’t see how you can be “contrarian and right” without poking holes in the myth of the A player.

This might insulate founders from feeling insecure and not pushing ahead because they don’t have all the cool qualities they think VCs are looking for.

It might allow startup ecosystems to start valuing being off the beaten path.

It would cause seed-stage funders to question their shorthands and filters which rarely get questioned in the rush to be “in the know”.

Those quality filters are doing the exact opposite of what they’re supposed to. They’re filtering for consensus picks when they should be filtering for contrarians.