This is part 5 of a series that walks through the slides in a pitch deck. See Start With the Problem, and Your Startup’s DNA: The Solution Slide, How Not to Waste Your Product Slide, and Why Now: Change is the Key to your Pitch.

The frustration of market sizing

The graveyards of pitch decks are littered with bad market slides. Entrepreneurs are not rigorous enough when they calculate market size. Investors expect too much rigor and precision for what is essentially unknowable. This makes the market slide a high-risk part of the pitch. A discussion about the size of a market should really be a discussion about assumptions. What are the assumptions that make a founder excited about this market?

Rather than rehash all the advice out there about market size, I’m going to focus on what makes this process difficult and how to think about it differently:

- What really goes into calculating market size

- TAM, SAM and SOM - Simplified

- How you should really look at TAM

- Redefining the addressable market

- Summary

Subscribe for free to receive weekly posts, a copy of my ebook Pitching a Leap of Faith, and invitations to my weekly Pitch Masterclass.

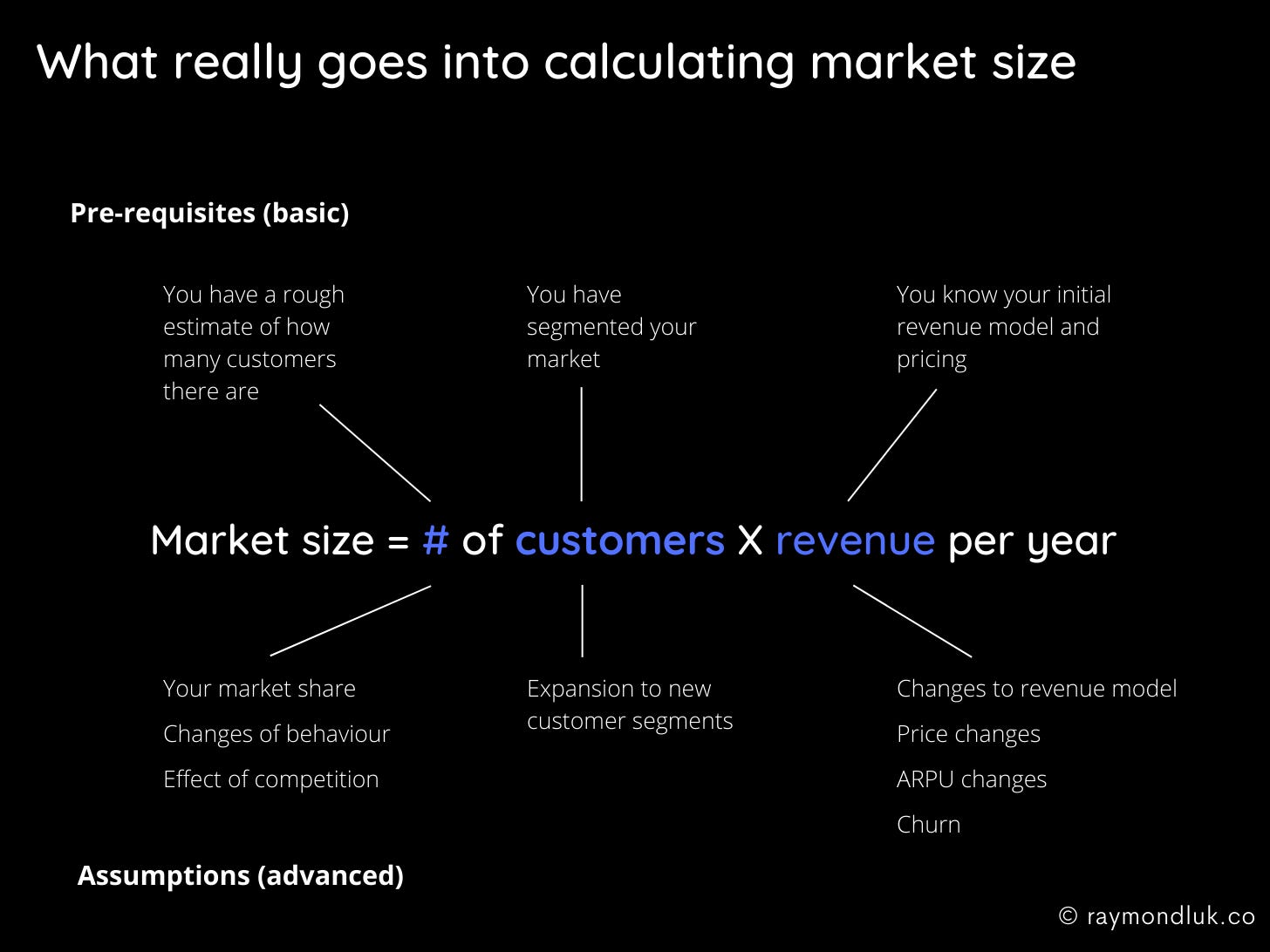

What really goes into calculating market size

The basic formula for calculating market size is simple: market size = # of customers X revenue per year. Easy right? Not really. There are a few pre-requisites and more than a few assumptions that go into this number.

Pre-requisites

Even the most basic market sizing needs you to segment your market (so you know who you are counting). Whenever I hear a pitch with “small business” in it I always respond, “small businesses do not exist.” You can’t count them unless you segment, e.g. restaurants, accountants, surf shops.

You also need to have an initial revenue model and pricing. Both, by the way, will likely change if you are just starting out. And those changes will have a big effect on the size of your market.

Finally, you have to get to the point where you can make a rough estimate of the number of customers. This will not be easy because you won’t find a research report with the exact number you want so you’ll need to make some leaps of faith in your numbers. You have to start somewhere.

Assumptions

A more advanced view of market size has to consider other assumptions:

- Numbers of customers - why do you think you’ll achieve X% market share? Over time, how will your customers’ behaviour change, for better or worse? Why won’t competitors start to encroach on your space?

- Customer segments - are you only ever going to sell to your initial target customers or will you expand?

- Revenue - is your revenue model set in stone or could it change? Are you assuming price will never change (or only go up)? Will the average revenue per user (ARPU) go up and why? Have you taken into account lost or churned customers?

I’m not suggesting that you can’t estimate the size of your market without knowing all of the above. It might be too detailed for the stage you’re at. But most people hearing your pitch will not take your market size on faith. They’ll have their own questions about how you got there.

All of this assumes you are calculating your market size using a bottom-up approach. The reason is simple: you won’t find someone else’s top-down analysis that matches your assumptions so it won’t match the story you’re trying to tell. Do the work up front and you will be better prepared to answer questions.

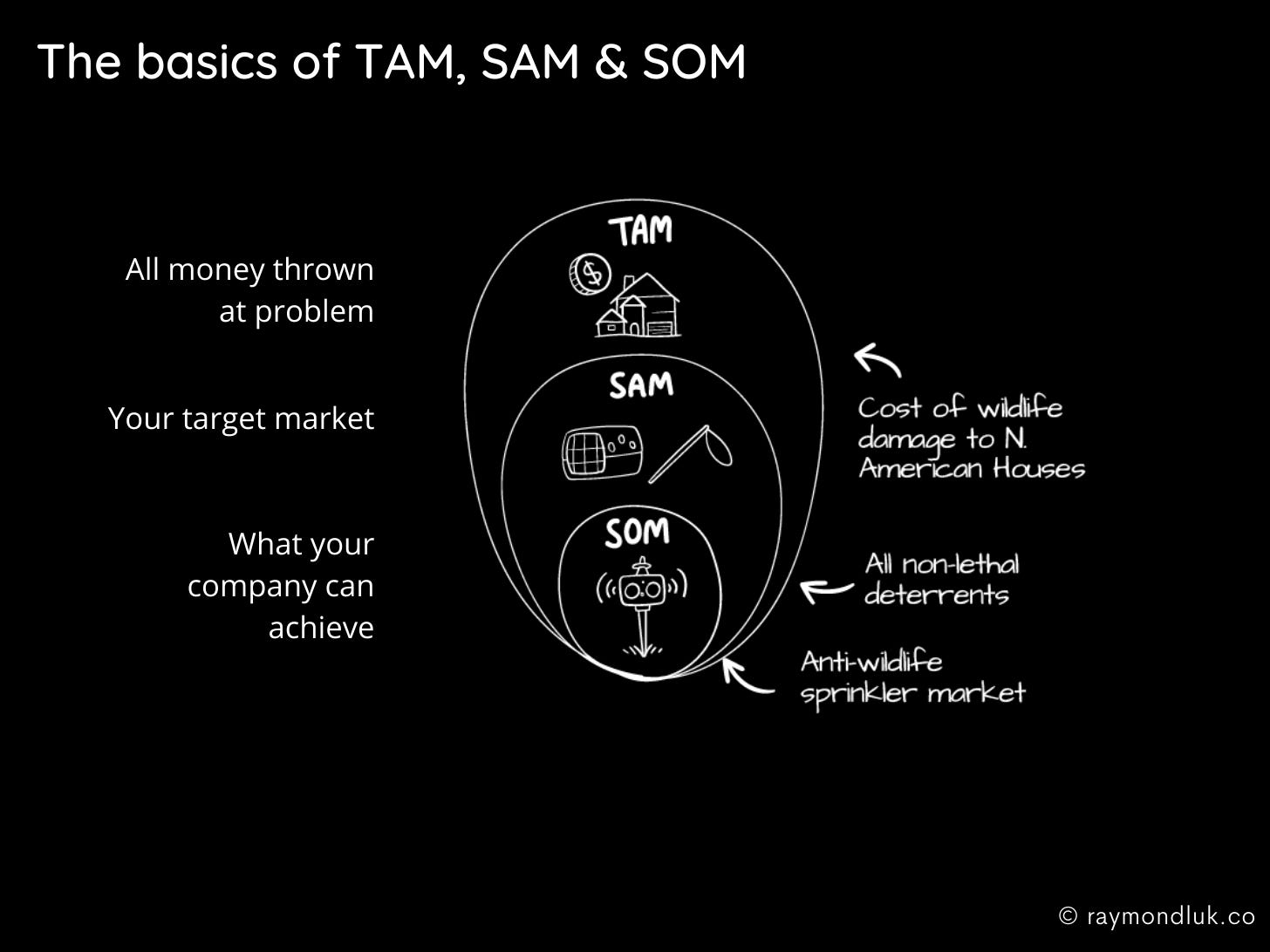

TAM, SAM & SOM - Simplified

You’ve probably heard the acronyms TAM, SAM and SOM as they’ve become a de facto standard. This model has ended up being more confusing than useful to entrepreneurs. In fact, many VCs don’t even know the definitions of the terms (from Pear VCs excellent article on market sizing):

But it’s still useful to know the concepts and you might end up deciding this is the best way to present your market.

My definitions are not the textbook version. I find it easiest to look at your TAM as “all the money thrown at a problem”, your SAM as your target market, and your SOM as what you think you can achieve.

Remember that many funders will not fully understand these concepts so feel free to define your terms.

You should be using this model to go from high level to low level. High level means talking about the general market environment, including technological or societal changes (see Why Now?). Investors want to know your vision for where you think the market is going.

Talking about SAM, i.e. your target market, is where you bring in concepts you raised in your Solution slide. What is your unique approach and who else in your market thinks the same way?

Finally, your SOM is what revenue you think you can achieve in the mid-term, e.g. 5 years. It’s your market share and the result of your go to market strategy and financial plan.

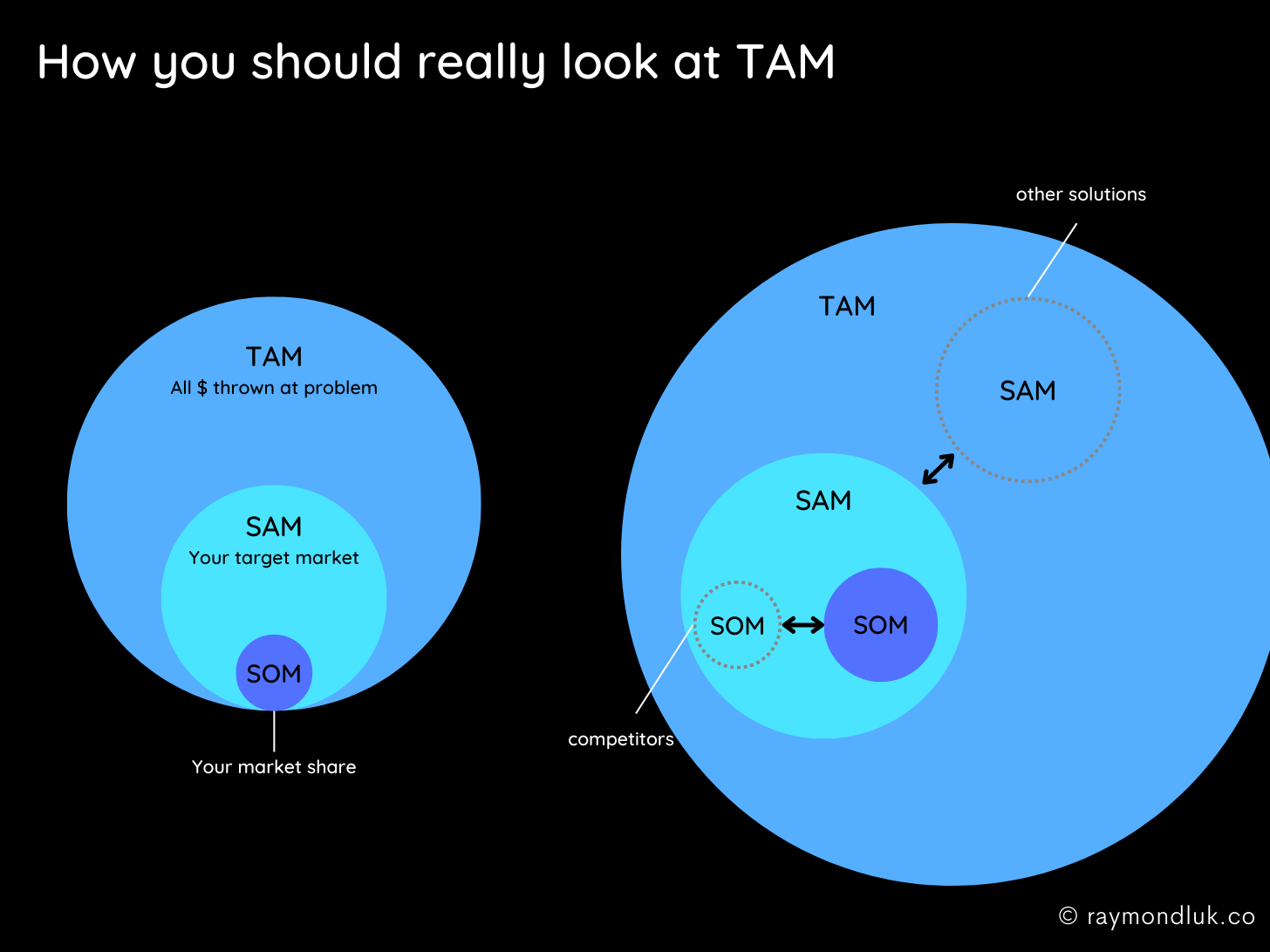

How you should really look at TAM

The standard way of displaying TAM, SAM and SOM (i.e. 3 circles) is deceiving because it excludes competitors and alternatives.

The illustration on the right is probably too complicated for your actual slide deck. But it’s useful to analyze your market this way to fill in gaps in your story.

- There are other SOMs in your target market. Those are your competitors. What effect will they have on you? What happens if more competitors enter your space?

- There are other SAMs too. Those are all the alternatives that exist to solving the market problem. New technologies or regulations can create new markets that compete with yours.

- TAM is not static. Markets can shrink, e.g. CD-ROMs, just as easily as they can grow. When you look at the total addressable market, consider how it can change. Ideally it’s growing. If so, be able to talk about how that benefits you.

Re-visualizing TAM, SAM and SOM this way is helpful because it helps you think through market forces and engage in a more meaningful discussion of the market beyond just saying it’s a billion dollars.

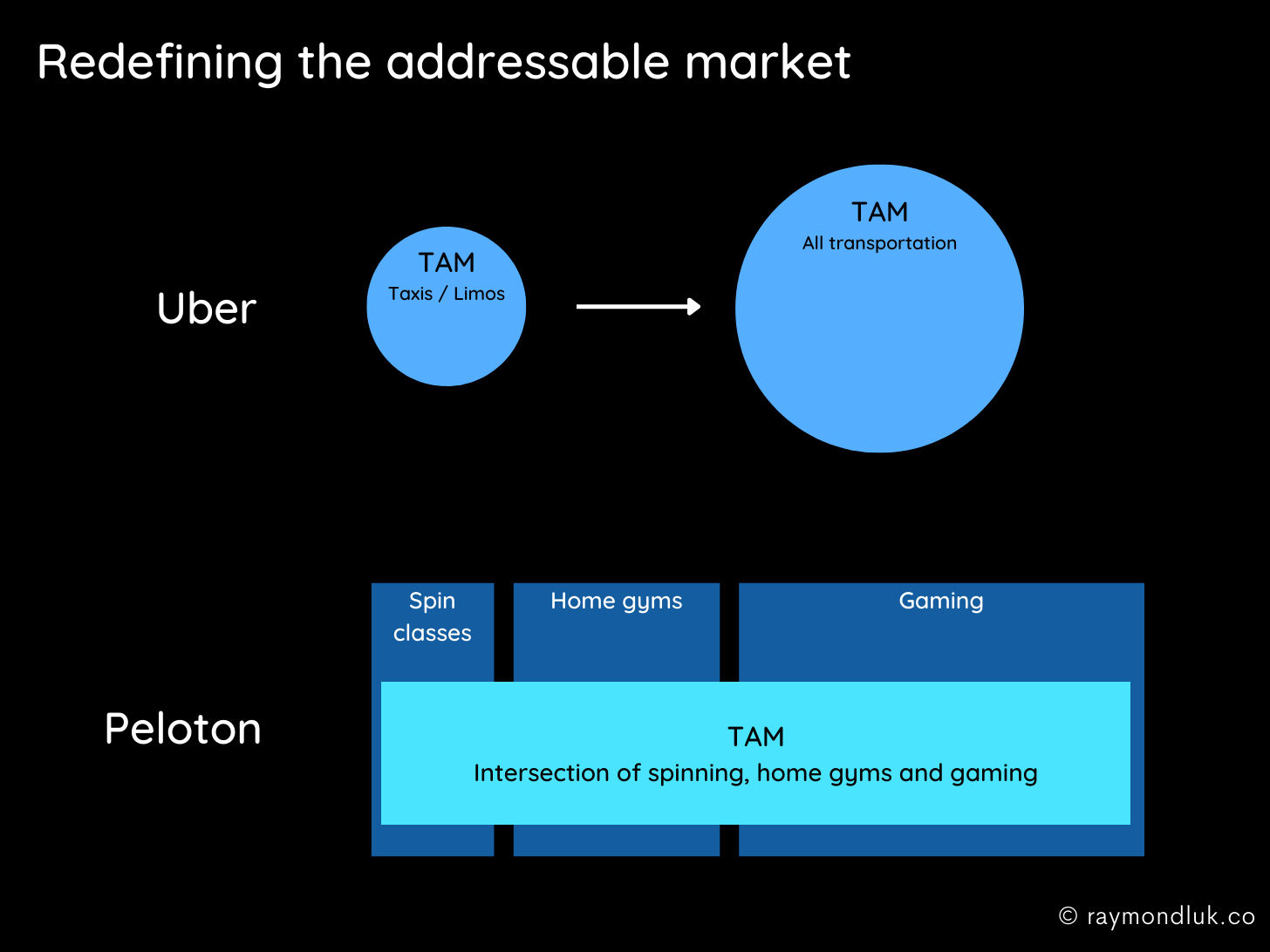

When you redefine the addressable market

In choosing to use the historical size of the taxi and limousine market, Damodaran is making an implicit assumption that the future will look quite like the past, Bill Gurley about Uber

This was investor Bill Gurley’s response to NYU professor Aswath Damodaran in a 2014 debate about the valuation of Uber. This highlights one of the key challenges, and opportunities, when it comes to market size: you are often creating or redefining a market.

Many founders struggle to arrive at a billion dollar market because they’re thinking too small. A disruptive product is likely to disrupt multiple markets in which case your addressable market is potentially much bigger. Here are two examples:

If Uber’s TAM was “all money spent on taxis and limousines” their SAM would be “ridesharing” and their SOM would be whatever they thought they could achieve vs competitors like Lyft. What Gurley is saying is this undervalues Uber because their TAM is really “all transportation”. Reframing the market that way massively increases the potential for the ridesharing target market.

Looking at Peloton, it would be limiting to say their market was only spinning or home exercise equipment. Their total addressable market is something bigger that is at the intersection of spinning, home exercise and interactive gaming. Reframing the market this way not only makes the market bigger but adds a growth dynamic, i.e. we think we can capture part of the massive gaming industry through our exercise-based interactive programs.

By the way, avoid using a Venn diagram when you talk about intersecting markets. It actually makes it look like your market is smaller (see, Geometry).

Summary - telling the market size story

In YouTube’s early pitch deck they talked about market size in terms of only two key drivers of video sharing:

There are no numbers on their slide (which I would not recommend doing in today’s fundraising environment). But however it’s presented, the story and thinking behind the market size is strong.

You can imagine the market growing as technology makes videos more and more popular. You can project how their initial target market (video search) might grow into live broadcasts, creator tools or original content.

Your mindset should not be to try to find the correct answer to “how big is your market?” No one knows. Do a bottom-up analysis then tell a story that invites investors to ask, “but couldn’t it be even bigger?”