When founders think about their runway I wonder how many are picturing landing vs taking off? Maybe because I’m a pilot but, as analogies go, it matters which one you’re thinking about. Reducing your fuel burn helps you have a safe landing but it doesn’t help you take off. And all startups are trying to take off.

When you’re taking off you need to burn more fuel to build up the airspeed you need to generate lift. Going slower won’t help because you’ll never achieve lift off.

I’m not advocating a higher burn rate by the way. I’m pointing out that startup lingo, like burn rate and runway, are shortcuts that do more harm than good.

This is important because these days everyone is rushing to explain how low their burn is. Does that really make you a more attractive company?

Thanks for reading A Leap of Faith. Subscribe for articles on pitching, funding and founder storytelling.

Most definition are wrong

Google “burn rate” and “runway” and you will get tons of articles that say this:

- Gross burn = cash expenses / # of months

- Net burn = gross burn - cash revenue

- Runway = cash in bank / net burn

It all makes sense. But what does the ‘rate’ in burn rate mean? It’s usually an average of what you spent in the past.

What if you spent $1k/month in the past, are spending $50k/month today and are planning to spend $100k/month in 3 months? What’s your burn rate?

As a shorthand, burn rate only works if you have predictable cash flow. That’s not the case for early stage startups. So dividing cash available by some average burn obscures the truth.

Fred said it best

Back in 2011 Fred Wilson wrote what I still consider the best overview of burn rate. He used the same broad definitions but reminded people this is a short cut, the “back of the envelope method.”

If you read his article you’ll notice that most of the time is spent talking about the exceptions to the shortcut. There could be irregular cash outflows like capital expenditures. When you get paid might not be the same as when you recognize revenue.

Burn rates can change pretty quickly. If revenues are ramping faster than expenses consistently month after month, the burn rate will go down. And for good reason – the company is getting closer to making money, which is what all this stuff is about at the end of the day. Burn rates can also go in the other direction if expenses are ramping faster than revenues or if there are no revenues. Burn rate calculations need to take into account the fact that burn rates aren't constant. If your burn rate is going up, from $83,333 per month to $100,000 per month, then the $250,000 you have left will not last three more months. It might only last 2 1/2 months. Assuming a constant burn rate can be very dangerous. Always know if your burn rate is going up or down and include that fact in your analysis.

If assuming a constant burn can be dangerous it really calls into question why people use it at all. In the end you need your own analysis and your own answer to the burn rate question.

Burn Rate Doesn’t Matter

Another critic is Scott Nolan from Founders Fund who wrote the next great burn rate article in TechCrunch in 2015, called Burn Rate Doesn’t Matter.

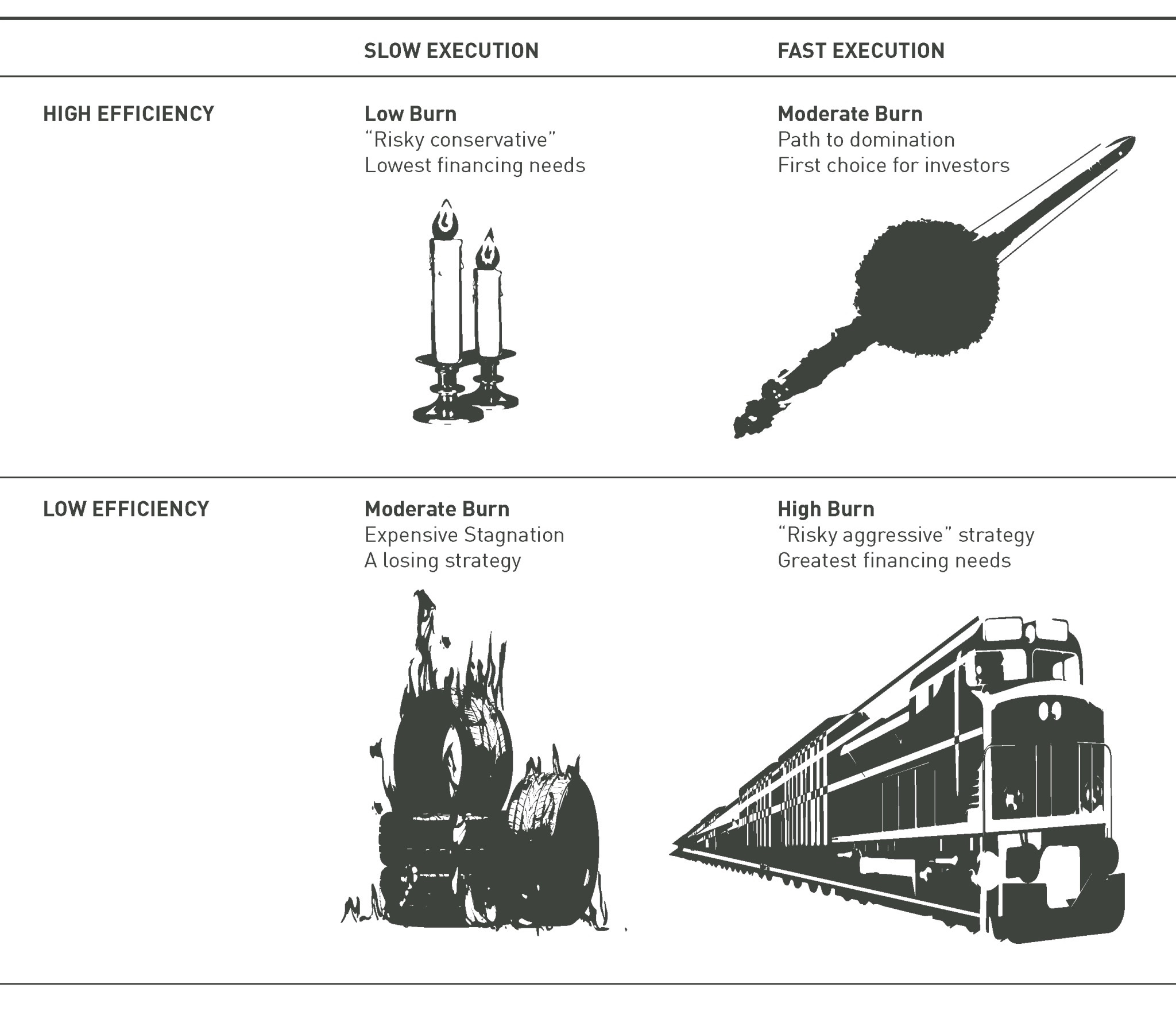

He calls burn rate a vanity metric. Cash burn is viewed positively when the cost of capital is low, and negatively when bubbles burst. What founders and VCs should care about is the rate of execution, or the rate of achieving important milestones.

I love this clarity and it’s disappointing how few people talk about this type of velocity.

A low burn rate can lead to a slow death or lost growth opportunities. A high burn can mask poor execution. As his framework shows, the ideal company has a moderate burn because it is highly efficient and fast. For this startup, artifically lowering the burn rate is “an attack on progress.”

What I find refreshing about this approach, which is still just as relevant 8 years later, is that it’s not dependent on the external funding environment.

Regardless of investor sentiment, great companies have to spend money and shouldn’t be afraid to pitch a growth story that requires capital. But it has to be rooted in ruthless execution.

Using the Projection Canvas to talk about burn rate

I introduced the Projection Canvas as a simple but rigorous way to build up financial projections. It’s also a good way to understand and talk about your burn rate.

A Projection Canvas already contains your thinking about what future milestones are important and have the potential to change the company. This will impact your expenditures and revenues, i.e. your burn rate.

Having assumptions transparently laid out in one place also helps you feel confident about answering questions about your burn rate.

You might decide to take all of your projected cash outflows into account and plan for a worst case scenario timeframe. That total cash outflow divided by your worst case scenario timeframe gives you an average projected burn rate that gets you to your next milestone.

Or, you might decide not to answer with a single number, but to speak to an actual cash flow projection taking into account future changes to expenses, revenue and one-time outflows. That’s going to be a more in-depth story. You can still have a single answer about your runway, but be able to go into more depth to explain how you got there.

Another advantage of building up your story from the ground up is that it addresses an important concept: optionality

Optionality vs burn rate

A major weakness of the burn rate discussion is that it reduces things to a predictable, and wrong, number. It ignores the fact that founders can and will adjust as they go along.

Given the right momentum, founders may decide to increase burn to go faster even at the expense of runway. Or they might slow down expenses and growth to buy time to close a funding round.

The point is there’s been very little discussion about what levers founders have to manage burn. Good founders think about those every day.

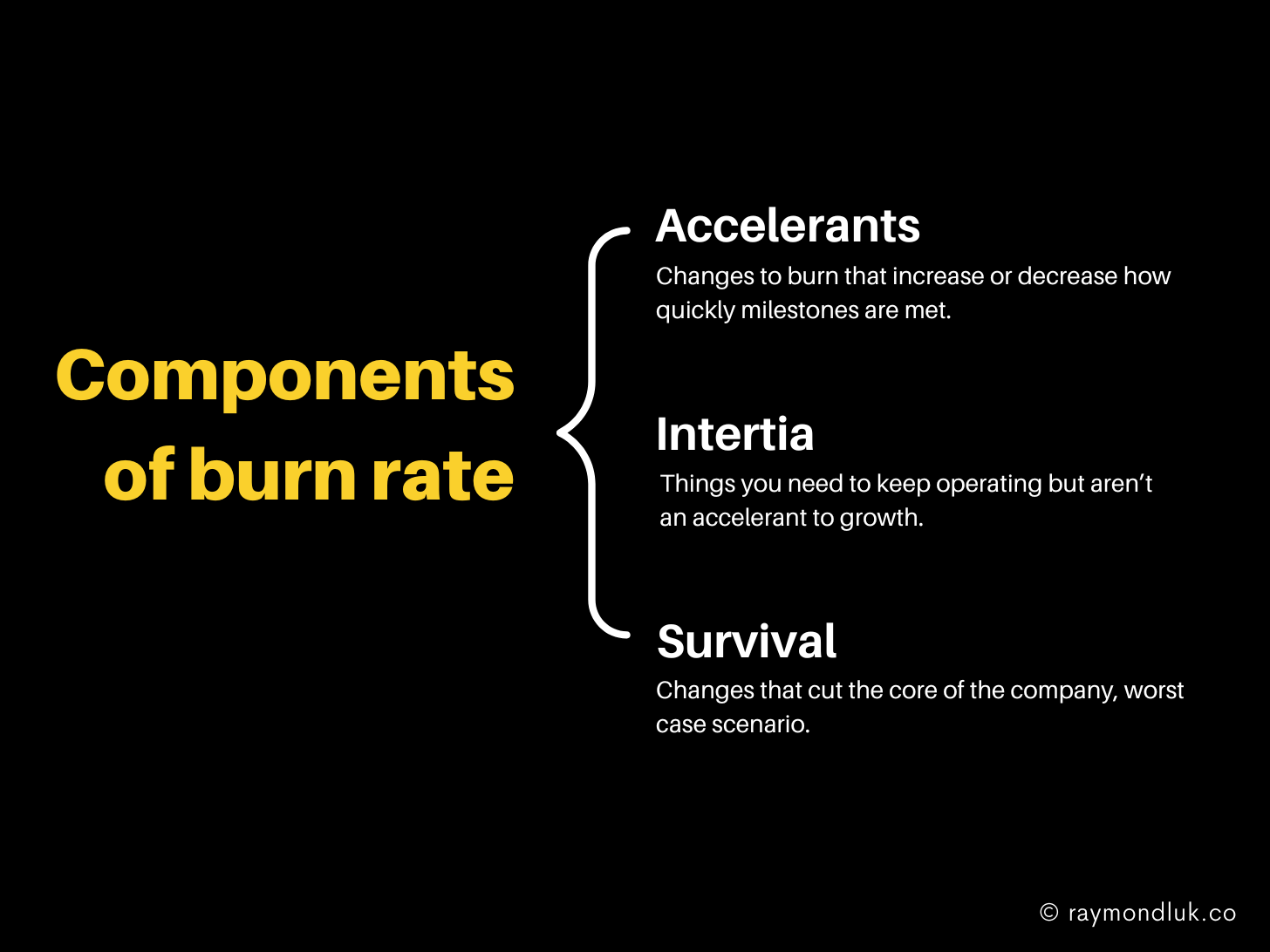

Instead of a single number for burn rate I think burn has 3 components that you need to think about:

- Accelerants - These are changes to burn that increase or decrease how quickly milestones are met. These should be as high as possible, given enough capital. If you focus too much on reducing burn and you don’t talk about accelerants, you are limiting yourself.

- Inertia - Things you need (or think you need) to keep operating but aren’t an accelerant to growth. No one will ever admit to doing things that are “nice to have” but the fact is you don’t learn about what you can live without until you survive a downturn.

- Survival - These are changes that cut the core of the company, like founder salaries, key personnel or important projects. This is the last place to reduce because you’re starting to amputate important limbs. But sometimes it has to be done, and I’ve done it. It comes at a cost.

This is not a post about how to find areas to reduce burn, but a discussion about understanding burn in a deeper way.

Breaking down burn rate into these components has an advantage. It allows you to separate what you can reduce to be prudent and what you don’t want to reduce because it decelerates your progress.

Always keep the focus on what milestones you can achieve. To achieve liftoff that’s all the runway you really need.

Learned something from this post? Please share it.